in memory of

Mara Padilla

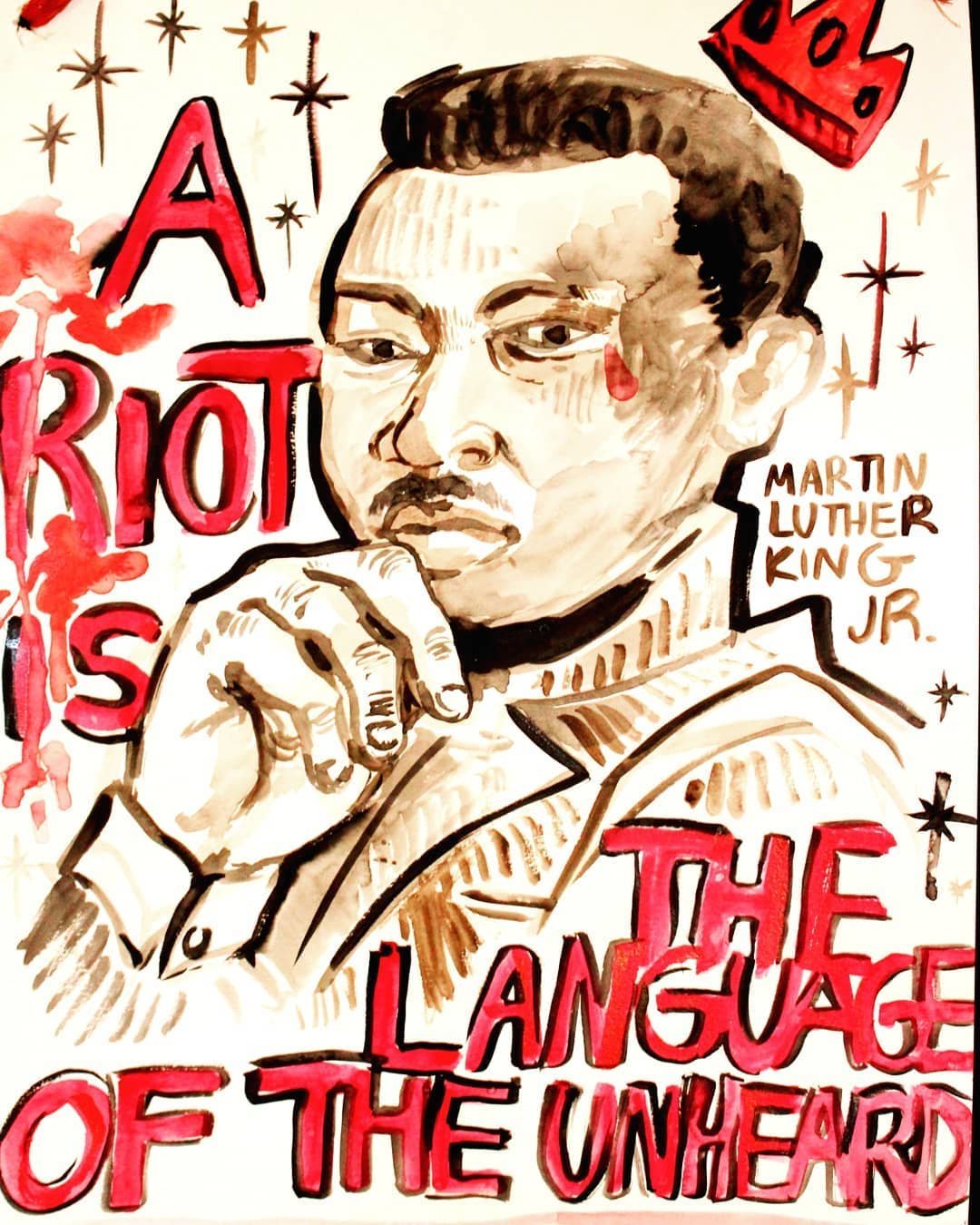

philosophic graphic Novelist, illustrator, painter

Padilla’s work has been featured in Dirty Diamonds issues 9 and 10, CUIDADO, and DONE issue II where her bio describes her as “a seasoned illustrator whose art has always tended to revolve around purpose, whether that be through thought-provoking illustrations or meaningful protest.”

Her portfolio spans across two instagrams, @marannie and @agirlwithonearm_.

note

This issue’s featured artist is unlike any other we’ve championed here at Blood Tree. Not only were we already familiar with Mara as a talented creator capable of white-knuckling your heart with a death-defying grip, but also as a friend and peer from our time together at our alma mater (for better or worse) Santa Fe University of Art and Design. If not for her medical leave and, moreover, the school’s untimely demise in 2018, we would have all walked that final stage together, red robes swaying in the high desert wind.

Upon hearing of Mara’s passing in late October, we instantly knew she would be our Issue 10 feature. However, there was one mild concern. We didn’t want the timing of her passing to be the main point of relevance given the issue’s theme, RE:UNION. While compiling the issue, it grew increasingly obvious this couldn’t be further from the case.

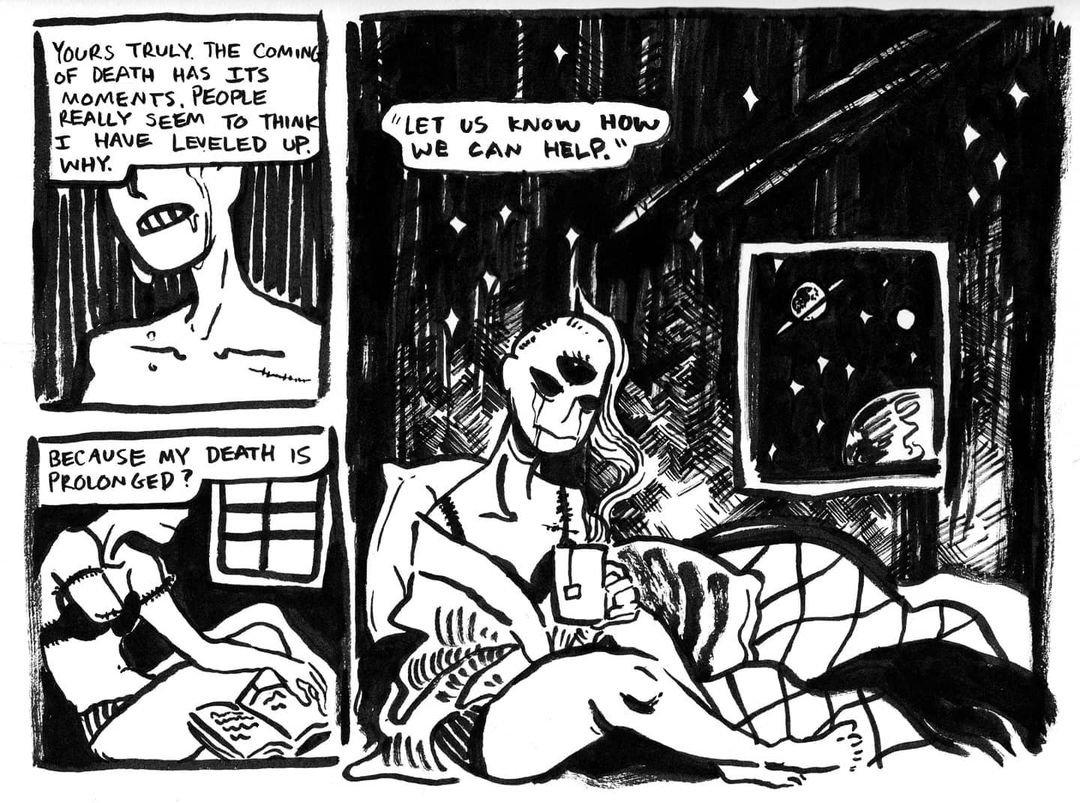

Mara unionized and intertwined concepts of sex and love with death and horror, religion and spirituality, destruction and demise. Within the fiery obstinance and impassioned philosophy formulated through her illustrations lies the very core of Blood Tree, a home for revolutionary artists whose radical ideas may not fit so easily into just any conventional space—and pridefully so. This journal was founded atop the rubble of norms, much like Mara’s work. We are beyond pleased to have her represent our milestone issue.

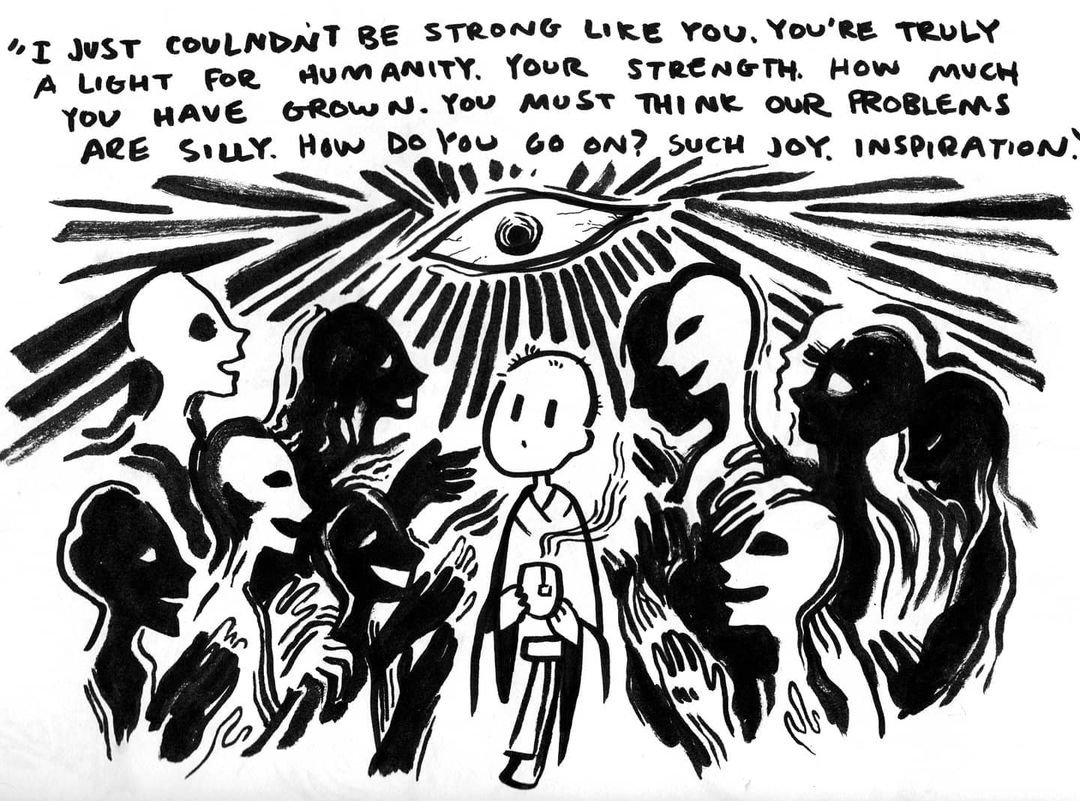

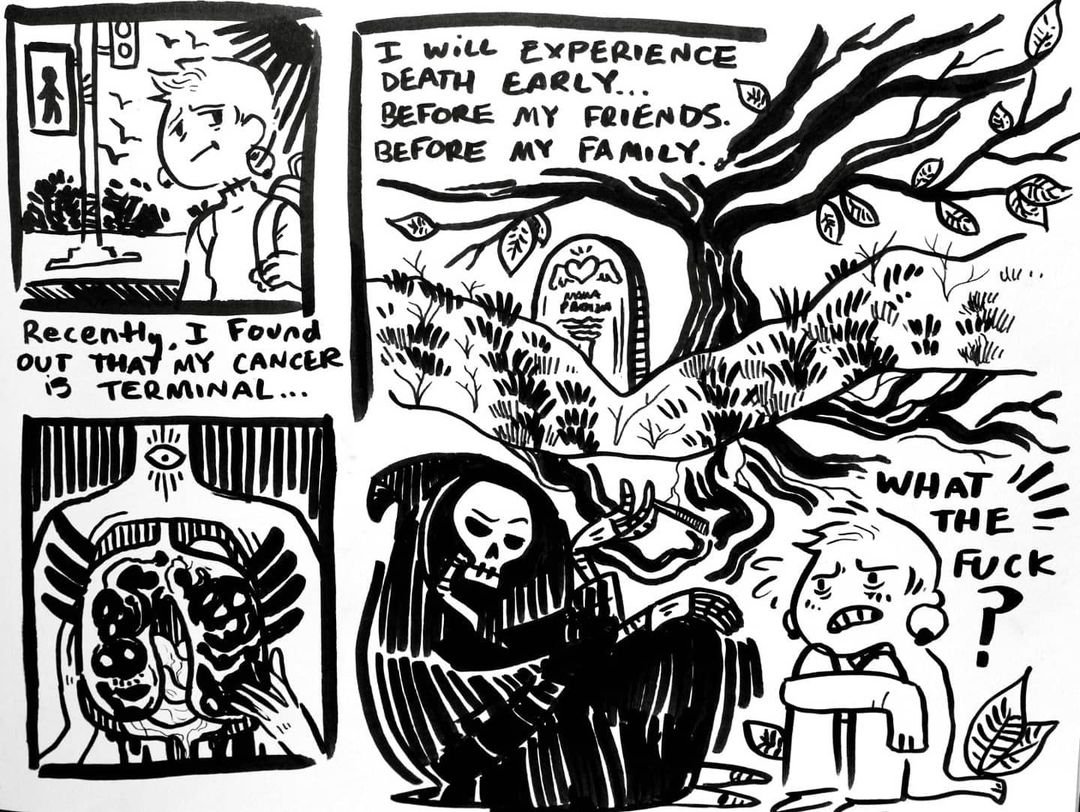

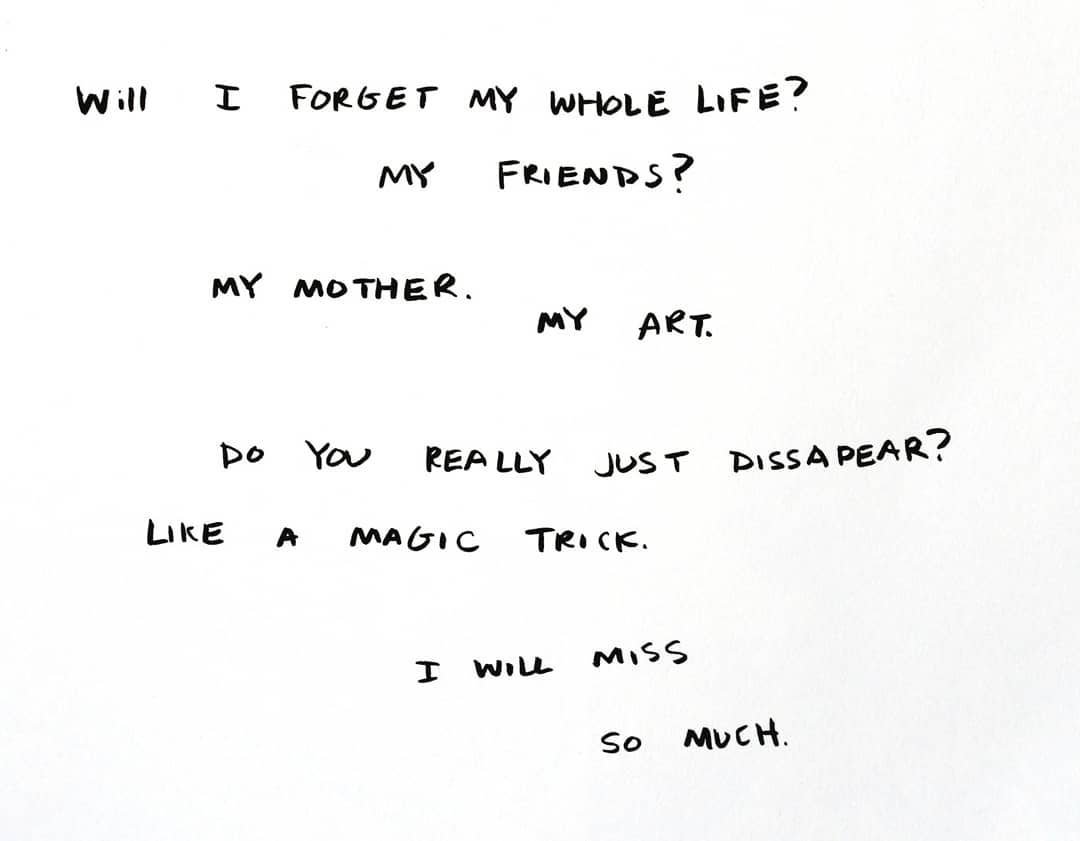

The themes throughout her comics read as both middle fingers to social customs and pleas for evolution—evolution of self, government policies, civil rights, the perception of god—and are just as diverse as the mediums through which they are made. White ink on black paper. Black crayon, sharpie, graphite on white. Acrylic, watercolor, ink wash and gouache. There’s not a box big enough nor page long enough to contain the expanse of Mara’s mind, so we shall take one from her own sketchbook and explore, without expectation, the world inside her head.

-Brantlee Reid, Founding Editor

In your average tribute, you can guarantee an overabundance of outplayed platitudes to drive tears down the faces of loved ones. They could light up a room with their smile. They are in a much better place now. God rest their soul. Friends and family nod along as if surface-level sentiments could ever be deep enough to hold the weight of their grief.

But Mara Padilla was lightyears away from average. It only takes a quick peek at her work to see how contrived clichés seared her soul like branding irons from such deprivation of imagination and truth. In this case, the only thing clichés would drive is Mara to insanity.

So, with all due respect, fuck that.

Of the people she did not find utterly exhausting was her best friend and soulmate, Gaeli Weiss, another student at SFUAD. “For the most part,” Weiss writes, “I think she found these comments annoying and unnecessary rather than mean-spirited. Mara's whole life, as far as I knew, she had been treated like fine china and she hated it.”

Though just under five feet tall, her voracious energy seemed to span miles beyond her height and age. “She hated being picked up or made to feel small or incompetent. And people honestly treated her like that a lot,” Weiss says. “I don't think that improved with getting cancer because then she was seen as small AND sickly and smothered [in] titles like 'brave' and 'courageous' which almost felt like antonyms. I think she found respite in being a bit of a contrarian.”

“She despised when people would say someone ‘lost’ their battle with cancer,” Weiss continues. “Like, they're dead, why also call them a loser?”

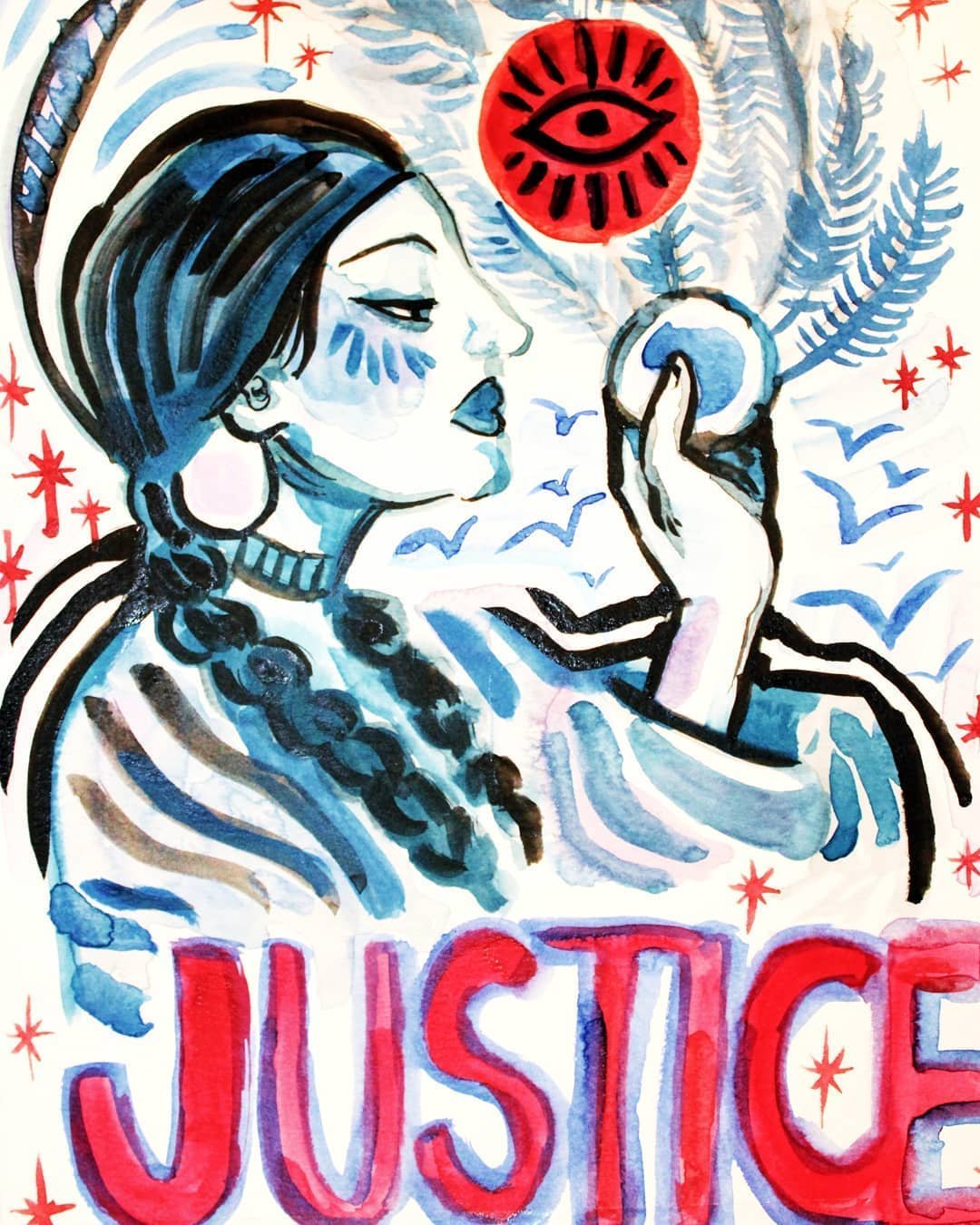

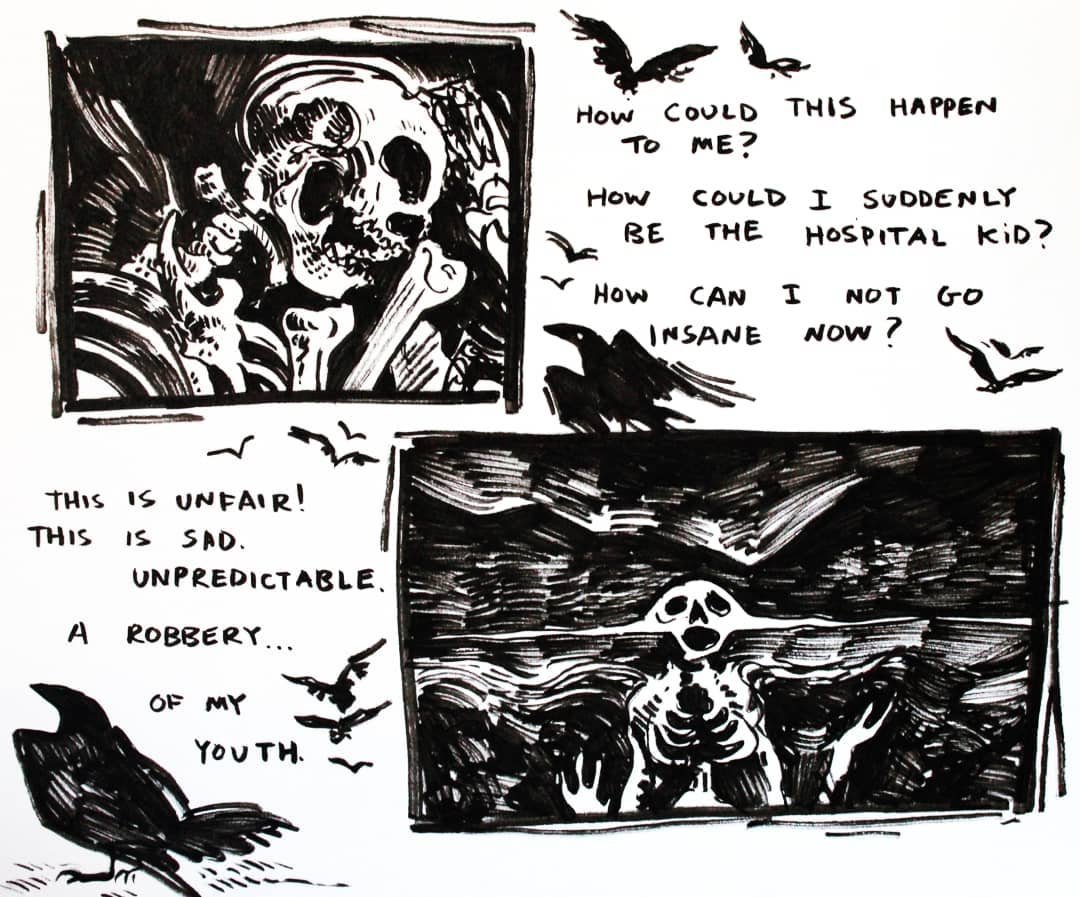

Mara was a lot of things—an indigenous socialist, an impassioned advocate for civil rights and drug policy reform, a connoisseur of the mystical and macabre facets of life, an open-minded, fire-hearted, free-spirited artist—a loser or victim she was most definitely not. Angry? Yes. She was rightly frustrated with the world because, simply put, it didn’t add up. Her personal reality was rife with confusion and questions she’d never find the answers to in this life.

The reality of the world at large wasn’t any more comprehendible. Only a couple months after discovering her cancer was terminal came the death of George Floyd. “Mara was loud and furious and heartbroken every time an officer was allowed to get off after murdering someone or a treaty was broken in favor of destroying land and resources that belonged to indigenous people,” Weiss writes. “Early in our friendship she had a polite way of articulating these beliefs and feelings. But the further along she got with her cancer, the fewer shits she gave about how people would perceive her anger.”

One of her panels reads:

“I think about how stupid humans are. If we just worked together, we’d be in the stars beyond our universe. Instead, we create more monsters for ourselves.”

That said, anger was far from her defining feature, but a propeller. Above all else, Mara’s positivity in the face of the unfathomable was the vehicle that carried her forward. Joseph Pinkerton, Mara’s boyfriend, can attest: “She was constantly true to her optimism and her desire to make art that touched on her illness and gave meaning to others in similar situations. At any moment she might take out ink and paper and create something immaculately styled and perfectly emotive, whether that driving feeling was loss or optimism.”

In her mother’s words, “Mara was her own advocate as far as navigating her treatment and educated others in the synovial sarcoma world, both nationally and internationally. I didn't always realize how far her influence reached but I'm learning that she wasn't just my little girl, but was so important to so many people.”

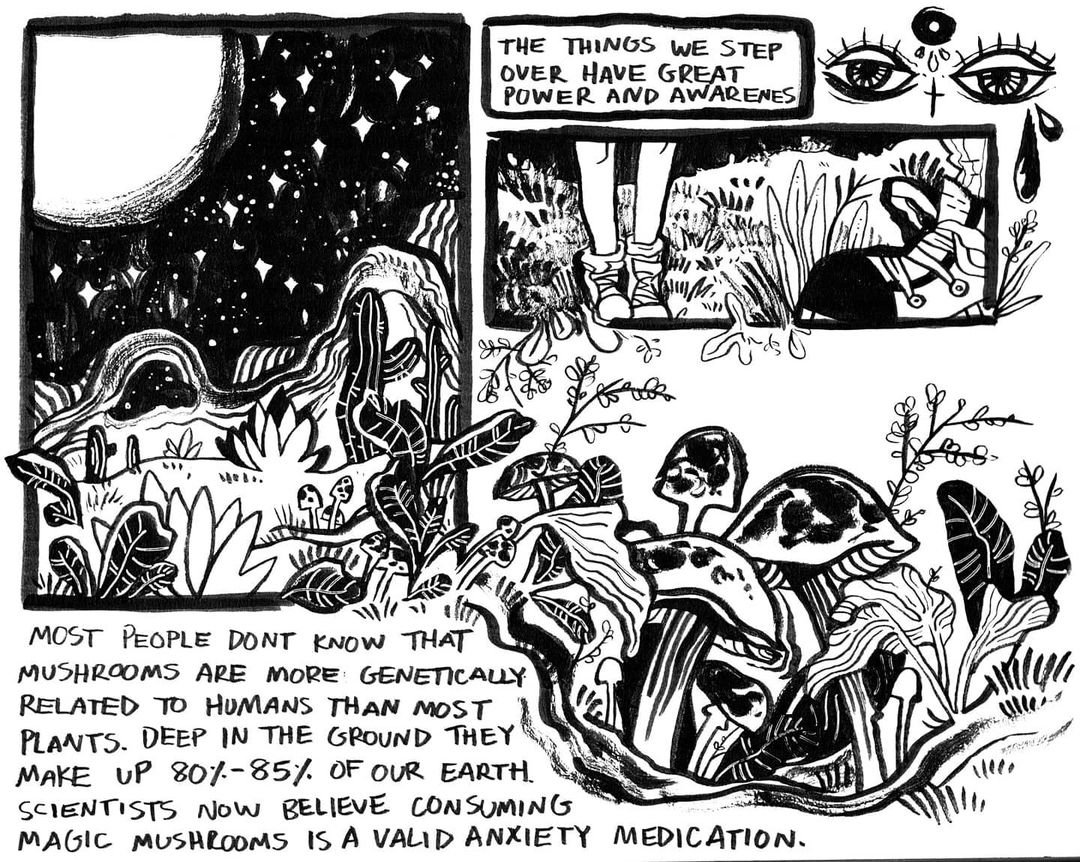

When asked to describe her general essence, Pinkerton says Mara was “kind without being weak, creative without being derivative. She had more motivation than a thousand others whose lives had no visible terminal point and she never relented,” and she channeled that motivation towards activism for personal and social causes alike, another being the mainstream acceptance of hallucinogens as a form of modern medicine, for the troubled psyche.

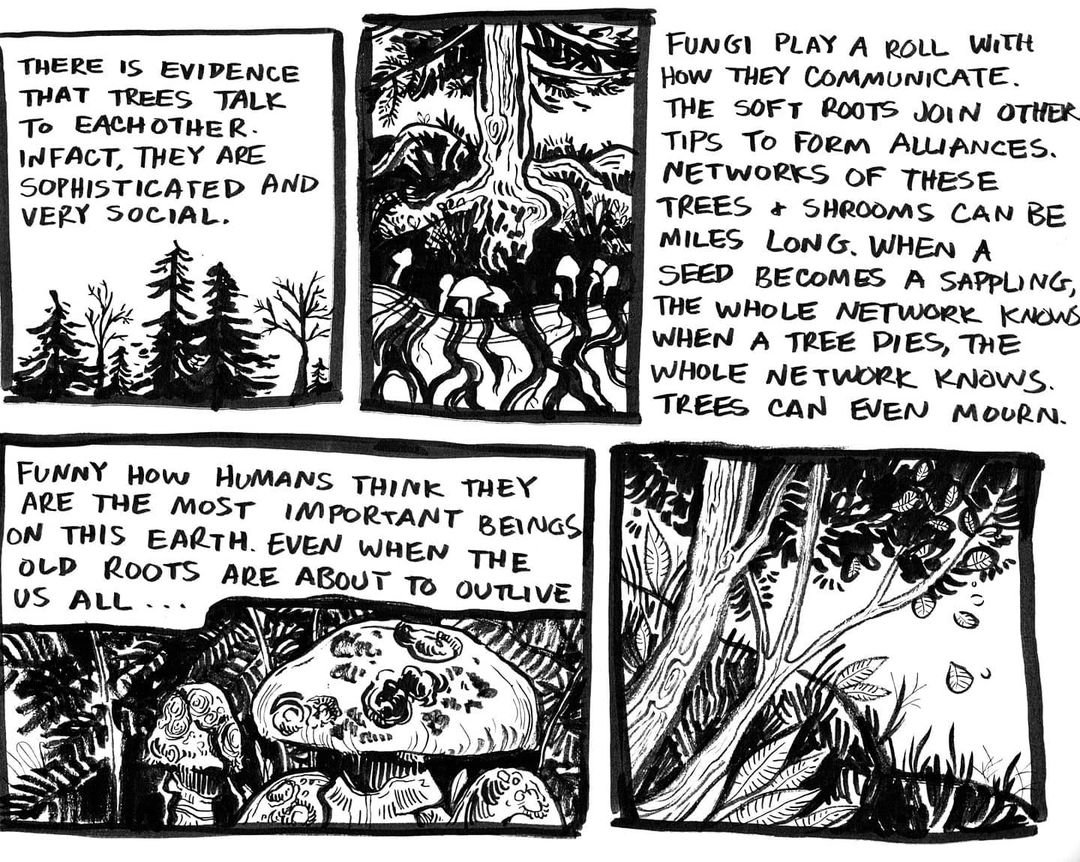

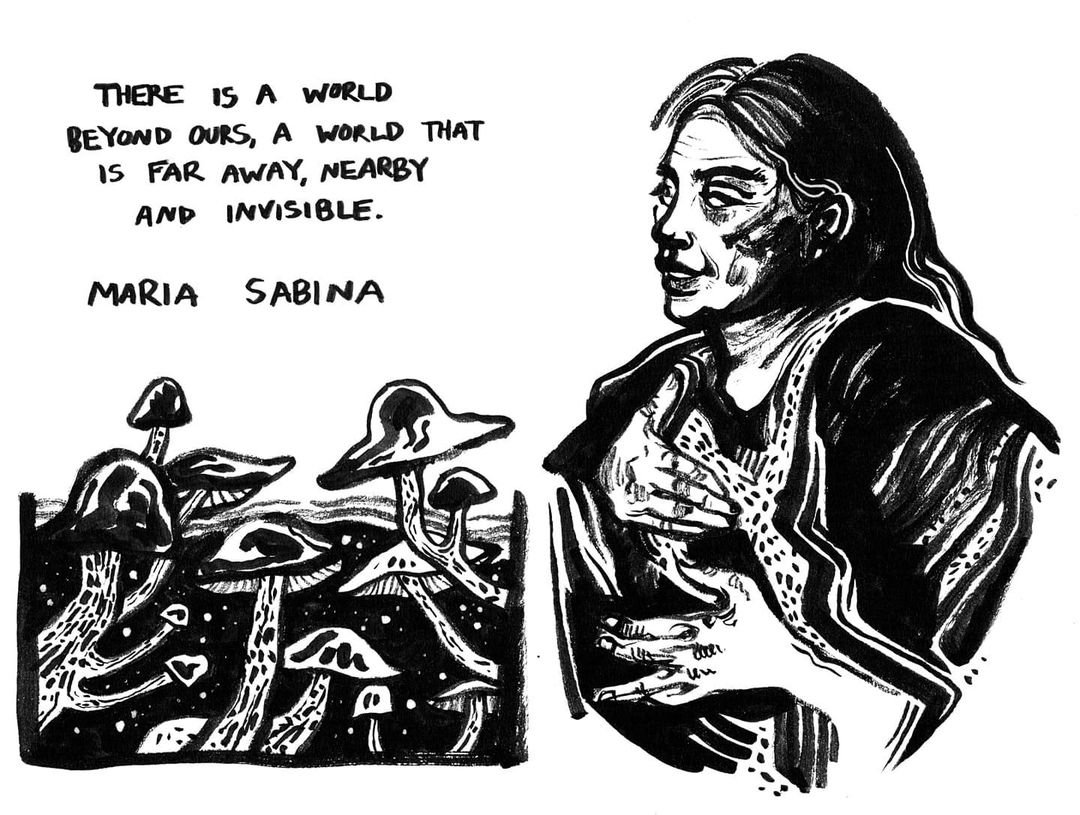

For her, the third eye-opening experience of mushroom and acid trips acted as a sort of roadmap into the normally unnavigable abyss. “It was a spiritual process for her as it is with so many,” Weiss writes. “The idea of other worlds, dimensions, things unseen to the average human eye had a special place in her heart. She talked a lot about aliens and ghosts. What they were and how they existed and in what capacity. Were they carbon based like us? Did they exist somewhere else? Would she be able to meet them some day, somehow? I think psychedelics were a gateway to some of that world.”

This is exactly what drew me to her illustrations in the first place. How they are unconfined, unbridled, uncompromising, just like her. They do not ask how you feel, for they do not care. They tell you how it is. They lament the way things are yet focus on what they could be. They make you think, what lies beyond the ether? Are we settling for antiquated mythologies when there is still more to discover? Can we change and evolve our current state of consciousness not only individually, but collectively? Are they one and the same?

In that delicate cross section between spirituality and religion, Mara navigates her undulating speculation on the afterlife with bracing frankness. I think it’s safe to say her idea of a higher power was not rooted in a biblical context, but rather in the tappable energy residing within all of us.

To scroll through Mara’s Instagram is to ebb and flow through her diagnoses and the perspectives that carried her down that ever-winding river into the unknown. Among all the obscurity, there was one thing she knew for certain: no matter how slow, fast, ravenous or placid, all rivers inevitably flow toward the sea.